A new College of Medicine is coming to D’Youville – Click here for more.

A Call to Service

Thirty-seven days after Japanese forces attacked an American fleet at Pearl Harbor, a short article in the Buffalo Evening News — 4,700 miles away on the opposite side of a country heading into war — made a plea to all women (at least 17 years old) to serve their country by enrolling in Red Cross nursing classes in Lackawanna. Before the attack, fewer than 1,000 women made up the U.S. Army Nurse Corps, so the call was desperate, as the nation’s military would grow from about 400,000 to 16 million in the next four years.

Six months into World War II, tiny D’Youville College — then an all-women’s school with barely 275 students enrolled — answered the call. That spring, the college announced the launch of Western New York’s first four-year nursing degree program, and that summer in 1942, its first student, Beatrice Koch from Mount St. Joseph Academy, received the first $500 nursing scholarship.

While the war greased the wheels in getting D’Youville’s program — and several other programs throughout the country — off the ground in the fall of 1942, the idea to introduce a health science curriculum at what had been a predominantly liberal arts school was first born in 1934 with a letter written by two chaplains from E.J. Meyer Memorial Hospital (now Erie County Medical Center) in Buffalo. The two men reached out to the superintendent of that hospital, because they felt “young Catholic women” in the area should be “provided with an opportunity to carry on their non-profession studies surrounded by every approved Catholic influence, if they so desire.”

D’Youville and Canisius College were the only two Catholic higher ed institutions in Buffalo at the time, and neither had the programs (or facilities) to make it happen. D’Youville President Sister Grace Wechter was intrigued by the idea, and in 1936, she reached out to the Association of Collegiate Schools of Nursing, which invited her to attend a state conference in Albany that spring.

Wechter and D’Youville continued to pursue the program heading into December of 1941, when President Franklin Roosevelt declared war on Germany and Japan. Suddenly, federal aid became part of the picture as the government began to push for more registered nurses — at least 3,000 a month, initially. And while World War II was the catalyst for an increase in programs, more nurses were needed on the homefront, too, due to the rise in industrial accidents, union-backed health insurance plans for workers and the general improvement in the standard of living at the time.

Nursing is, in the best sense of the term, a profession, because it constitutes a service indispensable to man and closely bound up with his physical and spiritual welfare. The field of nursing has an educational content of high culture, intellectual and spiritual value and so much be regarded as a fundamental department of learning in any well-rounded education plan.

The American Journal of Nursing, 1939

D’Youville’s plan was to create a program that combined two years of pre-clinical coursework on campus, followed by two years of hands-on training. In January of 1942, the school brought in Sister Rosalie Ashline to plan and develop the new Department of Nursing. Ashline had previous experience both in education and nursing before becoming a Grey Nun of the Sacred Heart. She earned a Master of Science in Nursing Education from The Catholic University of America and served on the New York State Board of Nurse Examiners from 1936-38.

Her first challenge was finding a hospital to partner with the school for the 10-week summer session after their freshman year and for a full year of rotations during their third year. The school had to agree to only accept D’Youville students, allow D’Youville to control the educational process and had to agree to allow all science courses to be taught on the college campus. Of the seven hospitals on Ashline’s wishlist, A. Barton Hepburn Hospital in Ogdensburg checked the most boxes. The only problem (and a big one) was Ogdensburg being 274 miles away from Buffalo.

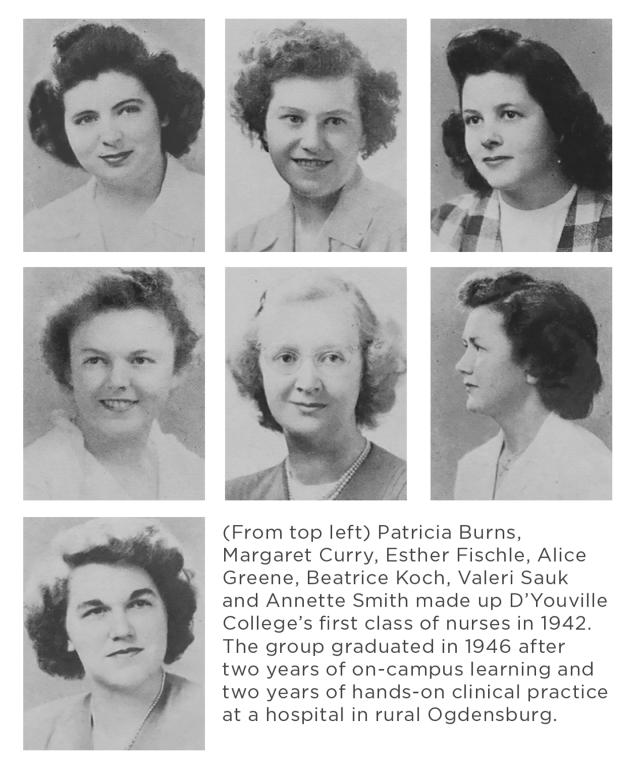

That fall, D’Youville welcomed eight students into its first class of nurses, seven of whom would graduate four years later — Koch, Patricia Burns, Esther Fischle, Valeri Sauk, Annette Smith, Alice Greene and Margaret Curry. Curry — who would return to the school after graduation to become an assistant professor of nursing and eventually the School of Nursing’s general chairman in the 1960s — recalled that first summer in Ogdensburg, which had just over 16,000 residents during the war.

“We went to the country, and none of us had ever been away from home,” she said. “It was exciting, though, because we actually got in and took care of patients. We had a set time to go to bed and to get up. We had to go to Mass every morning, before we went on duty. It was a lot like being in the Army.”

While on campus, those students enrolled in a good mix of liberal arts and health science courses. Religion, philosophy, ethics, English and history were joined by nursing history, anatomy and physiology, pathology, psychology, biology and nutrition and diet therapy. The clinical experience featured surgical nursing, care of children, operating room technique, maternity care, psychiatric nursing and — a sign of the times — tuberculosis nursing. Emergency room and public health nursing were added in the 1950s.

Prospective nurses at D’Youville had to be at least 16 years old and have “satisfactory references” in regard to their health, character and ability. They had to undergo annual physicals from a doctor (including a chest X-ray) and agree to vaccinations against smallpox, typhoid fever and diphtheria.

As for cost, during the 1940s, tuition was roughly $250 for freshmen, $250 for sophomores, $30 for the 10-week summer session and $10 for a public health affiliation. The third and fourth years cost $50 and $25, respectively. Other fees were included for library access, laboratory equipment and textbooks.

We were very nervous during the war. There was a very, I want to say, 'religious' feeling. We were concerned for the people who were suffering or dying. It was rough, and we spent a lot of time in the chapel and a lot of time with the chaplain. It was a rough time for all of us, because we were young and [emotional]. Our young men were over there, and a lot were dying or coming home hurt. We were praying for them all the time.

Quote from The D'Youville Family Album

Colleges and universities all over the country felt the impact of World War II in 1942. While D’Youville — being an all-women’s school — didn’t take on the enrollment hit like co-ed schools, life on campus changed dramatically. Blood drives became the new “social gathering,” and D’Youville women raised $75,000 in war bonds that year to pay for a pursuit aircraft that would be named for the school. Students took part-time jobs in local industries to help with the war effort, and even in their free time, students’ thoughts stayed overseas (one story had a young woman knitting an afghan to donate to troops as she listened to a lecture in English class).

Adding nursing to the curriculum was another way D’Youville could help.

The school was one of hundreds to benefit from the Bolton Nurse Training Act, adopted nationally to address the wartime shortage, and the federally funded U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps, which paid full tuition, room and board to students who pledged wartime service. Posters and magazine ads went out all over the country featuring images of stoic, patriotic uniformed women and promises of a fulfilling career and a “lifetime education.” By 1945, the Army’s nursing ranks grew to 57,000, with cadet nurses assigned to hospital ships and trains, flying ambulances, field hospitals and general hospitals on the homefront.

The war brought on innovations in the profession — military nurses dealt with shock, blood replacement and resuscitation in real-life situations. Their service wasn’t without risk, as 201 U.S. nurses died during the war from accidents, disease, weather-related incidents and hostile fire; and 67 Army nurses became Japanese prisoners of war after the fall of Corregidor in the Philippines in 1942.

Of the seven trailblazing nurses in the first class at D’Youville, Alice Greene and Esther Fischle were the only two to serve in the military during and after the war. Greene served in Germany, and Fischle became a nursing instructor in the Philippines. And while she didn’t serve, Valerie Sauk’s nursing degree allowed her to become a stewardess for the first international flights by American Airlines, which required medical training from its staff on long flights.

Let me dedicate my life today to the care of those who come my way. Let me touch each one with healing hands and gentle art for which I stand. And then tonight, when the day is done, let me rest in peace if I help just one.

A Nurse's Prayer, by Teri Lynn Thompson

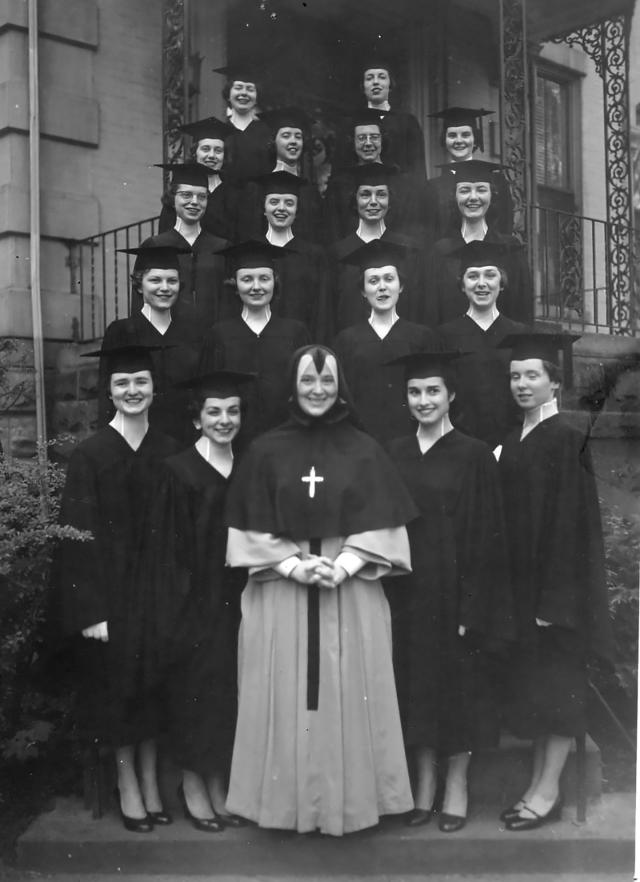

Under the leadership of Ashline, the department of nursing and its seven students blossomed into the School of Nursing and more than 100 students by 1950. When Ashline died suddenly in 1951, she was succeeded by Sister Francis Xavier, who also held undergraduate and graduate degrees in nursing from Catholic University. Xavier (who would go on to become president of D’Youville in the 1960s) led the school through its greatest period of growth in the 50s and established D’Youville’s first graduate program in nursing.

By 1962 — 20 years into the program’s existence — the School of Nursing had 270 students enrolled and more than 500 graduates living in every state in the country (plus Puerto Rico, Canada, France, Germany and Italy). At the time, Xavier attributed the school’s success to its focus on both professionalism and humanitarianism.

“We build the woman, and on top of that we develop her career,” she told the Buffalo Evening News in a 1962 article celebrating its 20 years. “The school of nursing tries to train ‘head, heart and hands’ — not just to teach a nursing student what she must do … but to teach her to think, plan, cooperate and manage, too.”

When Xavier was named president in 1962, she was succeeded by the School of Nursing’s first lay woman to be named dean, Virginia Ego. The program peaked in the 1970s with more than 1,000 full- and part-time nursing students enrolled at the school. In the 1980s, D’Youville leaders moved to reduce their dependency on nursing by adding more programs in business, computer science and education. Occupational and physical therapy were added in the late 1980s, strengthening the school’s health science programs but ultimately cutting into nursing.

Today, nursing is still the most popular undergraduate degree offered at D’Youville, and enrollment in the graduate program is right around the 450 mark. In 2017, D’Youville received a $2 million gift from Richard Garman and his family to name the School of Nursing in memory of his wife, the late Patricia H. Garman, who earned her BSN in 1976 and later taught nursing at the school. The gift was one of the largest one-time gifts in the school’s history and allowed D’Youville to expand and strengthen its program.

The COVID pandemic in 2020 highlighted the continued need for nurses in the U.S. and revealed a shortage that could hit 100,000 by 2030.

This summer, D’Youville named Dr. Shannon McCrory-Churchill as dean of the Patricia H. Garman School of Nursing after she served as interim dean and held a variety of academic clinical leadership roles during her career. The university said McCrory-Churchill’s focus on “student-centered learning, innovation in clinical preparation and dedication to addressing health care workforce needs” made her the right choice.

“She is the ideal leader to guide our School of Nursing during this critical time for the profession,” President Lorrie Clemo said. “Her vision for innovation in nursing education, paired with her passion for advancing access to healthcare and supporting our students, will ensure D’Youville continues to prepare nurses who are both highly skilled and deeply compassionate.”

MILESTONES

1942 | As the nation heads into World War II, D’Youville College — answering a nationwide call for more nurses — launches the first bachelor’s nursing program in New York.

1950 | Eight years into the program and four years after graduating its first class, the nursing department becomes the School of Nursing.

1957 | D’Youville launches a BSN completion program for nurses coming with with an associate’s degree and for diploma RNs.

1972 | A year after D’Youville College goes co-ed, the School of Nursing admits its first male students.

1978 | The School of Nursing enjoys its highest enrollment with 1,107 total nursing students.

1983 | The School launches its first graduate program in nursing — a Master of Science in Community Health Nursing.

1990s | Between 1989 and 2001, D’Youville launches a dual BSN/Master’s program, a Family Nurse Practitioner program, a five-year dual degree program and new post Bachelor’s certifications.

2010 | Nursing students embark on the School’s first mission trip to the Dominican Republic.

2012 | D’Youville’s Doctor of Nursing Practice program is approved by the NYSED.

2019 | After nearly 70 years as a school, the School of Nursing becomes the Patricia H. Garman School of Nursing, in recognition of her contributions to the nursing profession and her family’s generous contributions to the school.

—---------------------

ELEANOR ALEXANDER (’61 BSN)

“She was a goddess to us for volunteering for Army nursing. She was our Florence Nightingale.”

Those words came from Patrick Vellucci, who served in the U.S. Army’s 10th Calvary, 4th Infantry in Vietnam for two years beginning in 1967. That first year, he met a young nurse, Eleanor Grace Alexander, who joined the Army Nurse Corps earlier that year after starting her career at hospitals in upstate New York and in New Jersey before volunteering to join the war effort.

Alexander made it to Vietnam that June and was placed at the 85th Evacuation Hospital in Qui Nhon, where she cared for seriously wounded soldiers, both Americans and the Vietnamese. On Nov. 30, 1967, she boarded an Air Force C-7B transport plane with 26 others for a routine flight from the Cam Ranh Air Base back to Qui Nhon, about 165 miles away. As the plane approached their airfield, the pilot was advised the weather made landing unsafe and told the pilot to proceed to another nearby base.

Enroute to that base, the plane hit a mountain at 1,850 feet, killing all 26 on board, including Alexander. She was one of only eight military servicewomen (all nurses) and 59 civilian women (Red Cross volunteers and others) to die in action during the war.

Harold David Parks wrote a tribute for Alexander for the New Jersey Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial & Museum, and while he never formally met her, he remembered Alexander well: “She was the subject of admiring conversation by all of my enlisted buddies. She was always smiling and bright-eyed … when word came that we lost her, everyone was sad. We had lost other young from our unit, and we hardened ourselves against such losses and expected them. Capt. Alexander, however, was different. He loss was felt by everyone, and grief cast a cloud over the 85th.

“After we lost her … we all realized that she had made our lives in Vietnam a bit more bearable.”